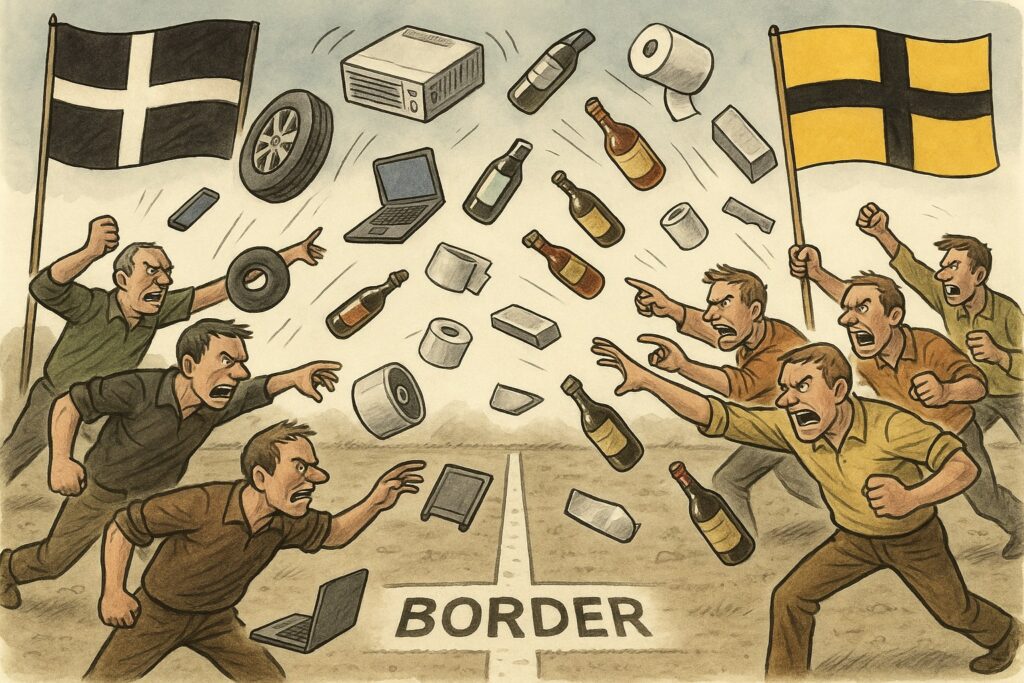

“Trade War” as a Contradiction in Terms

If a free country is defined as a place where an individual or private organization is free to engage in voluntary cooperation—including trade—with whoever is willing or able to and on terms accepted by both parties, it follows that “trade war” is a contradiction in terms. Free trade is peaceful trade.

Why is this definition of a free country useful? Why should we see individual action as inseparable from social life? For two sorts of reasons. First, a free society is desirable to the extent that equal liberty, along with the opportunities and general prosperity that follow (as economics demonstrates), are themselves desirable. Second, understanding the consequences of social interaction requires methodological individualism—that is, to start the analysis from individual preferences, incentives, and self-interest. In the context of our topic, it is easy to see the importance of individual motivations. Suppose that “France” and “Canada” stop trading. Only methodological individualism can explain the smuggling that will result.

There are justifiable exceptions to free trade when the very possibility of free trade is compromised—killer-for-hire contracts, for example, or the trade or ownership of slaves. Other restrictions can be argued for (see notably James Buchanan’s The Limits of Liberty or, co-authored with Gordon Tullock, The Calculus of Consent). That a state may restrict its own subjects’ liberty because another state ruler does the same, constitutes, at least in peacetime, an invalid justification.

All that is different if one believes that “countries” trade. A moment of reflection suggests that they do not. How can “France” trade with “Canada”? Neither has a brain, arms, or legs, with which it can choose to trade and approach the other with arms full of goodies to exchange. Nobody in his right mind, even with only basic information, can believe that this happens in reality. What most people (alas) intuitively believe is that the political authority in France trades with the political authority in Canada; or, in practice, that the political authority in a country decides with whom and on what conditions its subjects and their private associations may trade; and that there is no other society possible or desirable.

Outside of a free society, a trade war is just as possible as an all-out war. Often, if not nearly always in the history of mankind, the two sorts of war went hand-in-hand. The rulers of France and Spain could engage in war because it was in their interests to do so. Whether the rulers are elected or not matters little; what does matter is the scope and extent of their power. But note how methodological individualism is still essential to explain the rulers’ actions—to which extent, for example, they respect the international-law principle pacta sunt servanda.

******************************

“Trade War” by ChatGPT, with some guidance

econlib